by Yaakov Zinberg ‘23

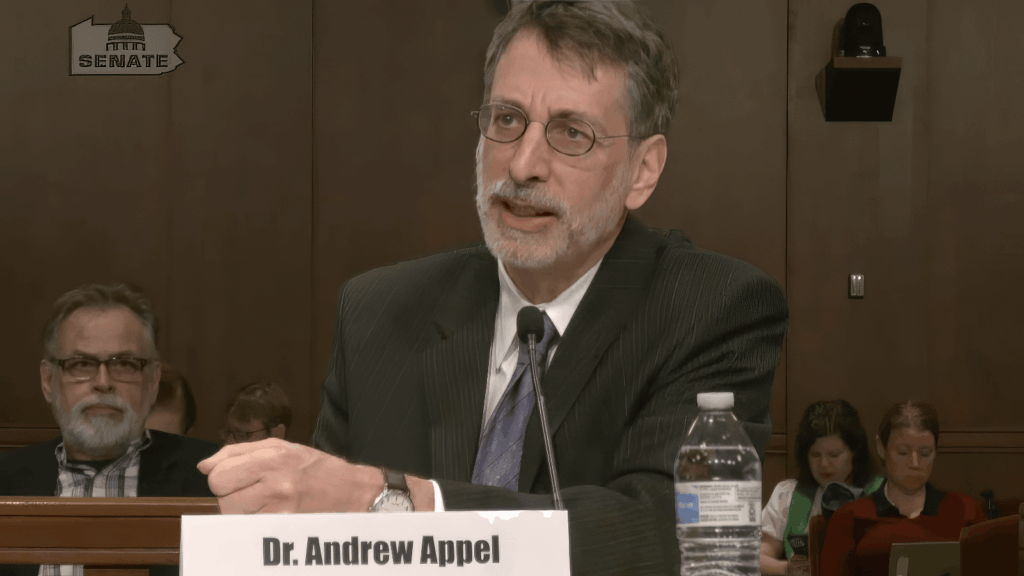

During the first week of the 2009 spring semester, Andrew Appel ’81, Princeton’s Eugene Higgins Professor of Computer Science, made the short trip down Route 1 to Trenton’s Superior Court. He was asked to serve as an expert witness in a New Jersey trial in which the state was accused of using voting machines that could easily be hacked—and therefore did not guarantee voters their right to have their votes faithfully counted. Appel had previously demonstrated that this could be done in a matter of minutes: all it took was replacing the machine’s read-only memory (ROM) chip with one containing a simple program that quietly shifts votes from one candidate to the other.

So when the defense attorney asked Appel during cross examination to put this to the test before the court (there was a voting machine in the courtroom), he was ready.

“I said, ‘Okay, I have my toolbox here,’” Appel recalls. “I took off my suit jacket and right there in the courtroom I started removing security seals, opening up the screws, replacing the ROM chip, and putting it back together,” all without leaving behind any evidence that the machine was tampered with.

It’s this straightforward, didactic approach to advocacy, coupled with a good deal of technical know-how, that has elevated Appel into a national expert on voting machine security—even without a screwdriver in hand. Before congressional subcommittees, on the news circuit, and, most consistently, on the pages of this blog, Appel has explained in simple terms the capabilities and vulnerabilities of the voting machine technology counties and towns choose for their elections, showing the general public that an otherwise esoteric detail of how our elections run could have profound consequences.

The evolving importance of the voting ballot

Appel retired from Princeton earlier this month, but plans to continue researching and speaking about voting security—work he began nearly 25 years ago.

“In the 20th century, no one cared that much about the technology of how we vote,” Appel explains. That changed when the 2000 presidential election came down to the status of the error-prone punch-card ballots that some Florida voters failed to fully punch, leaving behind the infamous and ambiguous “hanging chads.” Congress responded by passing the Help America Vote Act, which gave money to the states for upgrading their voting equipment, and many bought voting computers classified as direct recording electronic (DRE) systems, in which a voter makes selections via an electronic interface—usually a touchscreen—and votes are stored into the machine’s memory. The computer adds up the votes and prints the finals results after the polls close.

“Computer scientists could see immediately that this idea has a fatal flaw,” says Appel. “If a fraudulent program is loaded into that computer on Election Day, or is scheduled to take effect on Election Day, it can print out any numbers the programmer wants it to print out.”

There’s no evidence that a bad actor has ever exploited this to affect the outcome of an election, but the possibility is a major election security liability, according to Appel and other election security experts. The solution, they argue, is to use paper ballots marked with a pen that are fed into an optical scanner. Not only is the system less vulnerable to hacking than the electronic machines, but the paper ballots can be recounted or audited by hand if needed.

“The idea that you can affect policy in a meaningful and useful way by just explaining the science to county and state legislators was really true in this case,” Appel says. In 2006, nearly 42% of registered American voters lived in jurisdictions that used DRE systems for all voters; in 2024, that number hovered just above 5%.

By his own estimation, Appel dedicates 90% of his research towards formal methods for reasoning about programming and programming languages. But it’s the other 10%, spent on technology policy, and voting technology in particular, that Appel has written about on the CITP Blog since 2007, attracting a wide readership in the Princeton community and beyond. He’s given readers an in-depth look at New Jersey voting lawsuits; “the people of New Jersey are lucky to have Professor Appel in their corner,” commented one reader. In the leadup to the 2020 presidential election, he dedicated a number of posts detailing why Internet voting, proposed in some places in light of the Covid-19 pandemic, is impossible to secure and should universally be avoided.

“A tremendous mentor and a really big influence”

Within CITP, Appel is known as a supportive colleague and mentor, even as his profile has grown. CITP director Arvind Narayanan recalls how Appel sought advice on a grant proposal from him, despite the large experience gap at the time.

“That was very surprising to me that a very senior and famous professor would ask for feedback from me, a very junior faculty member,” Narayanan says. He also credits Appel for encouraging him to write a book pre-tenure, something Appel had successfully done (Compiling with Computations, published in 1992).

Appel, Narayanan says, has “been a tremendous mentor and a really big influence” on the direction of his career.

Predictably, political figures have tried using Appel’s research to suit their own agendas. He’s gotten calls from candidates who lost elections in which touch-screen voting machines were used, wondering whether they were cheated out of a victory.

“The first thing I usually say is, ‘Well, maybe more people voted for the other guy,’” Appel says with a smile.

Following elections, some commentators and public figures often reference Appel’s work in discussions about the integrity of voting machines, including unfounded claims that the machines may have been compromised.

He shrugs it off. “Once you publish something, it’s not up to you to control how people talk about it. You have to kind of let go of that,” he says.

But make no mistake. Appel’s blog posts don’t shy away from criticism: of specific voting machines that are particularly vulnerable, of judges who get the science and policy of voting wrong, and of election administrators who could do more to secure voting in their districts. It’s all in the interest of educating the public about how voting works and should work, without too much concern over how some might use or respond to this work.

“That has allowed us to do much better public policy research,” he says. “And it’s good to see that, in the year 2025, it looks like Princeton University is not easily intimidated either.”

Leave a Reply