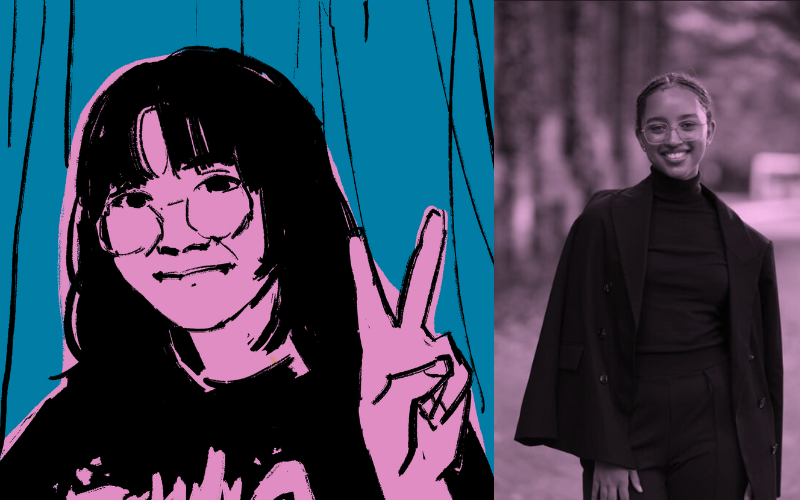

Mona Wang is a Princeton Ph.D. student in the Department of Computer Science and the Center for Information Technology Policy. Wang recently sat down with undergraduate student Tsion Kergo ‘26 for an interview where they discussed her research into surveillance technologies, what developed her interest in cryptography, and warns about the security risks of social media platforms.

Tsion Kergo (TS): Would you mind just introducing yourself and a little bit about your background and your research?

Mona Wang (MW): Yes, so I’m Mona. I’m currently a fifth-year PhD student with the Center for Information Technology Policy. I’m advised by Jonathan Mayer and Fatemeh Pahlevan. Generally, my research concerns surveillance—online surveillance and online censorship. I try to protect our rights to privacy and speech online. I do that by analyzing systems of mass surveillance and looking at how to protect our internet data. On the speech side, I measure network censorship and explore ways to circumvent it, again focusing on preserving our right to access information like academic content.

TS: Could you discuss a little bit more about your background? Is this something you were always interested in from undergrad into grad school, or did you come from industry?

MW: I’ve been interested in cryptography since undergrad. Around 2015, during my undergrad, I came across a white paper called The Moral Character of Cryptographic Work. It argued that cryptography is inherently political—it rearranges power and determines who has access to what data. That really stuck with me, especially in the context of the [Edward] Snowden revelations. It led me to focus on privacy and encryption. After undergrad, I worked for the Electronic Frontier Foundation [EFF]—kind of like the ACLU for the internet—where I advised on litigation and policy. That got me interested in the policy side of computer science, which led me to join CITP at Princeton.

TS: That’s good. Can you tell us a little bit about the research you’re currently working on?

MW: One major project looked at mobile encryption. While web traffic is mostly encrypted via HTTPS using TLS [Transport Layer Security], mobile traffic often isn’t. I found that many mobile apps either don’t use encryption or use non-standard cryptography, which can be easily broken. My team analyzed the top 9–10 most common non-TLS protocols and found nearly all were vulnerable to attacks. Interestingly, many of these insecure apps came from China, where different cryptographic standards prevail due to political and regulatory separation. So there’s this “Balkanization” of the internet, and Chinese apps were often less secure than others.

TS: How do you hope your work on privacy and surveillance influences actual policy or affects everyday users?

MW: Great question. First, we reported all these encryption issues to the companies, and about 50% fixed them. That has a real-world impact—these apps have hundreds of millions of users. It shows that technical audits can directly improve user privacy. From a policy angle, this could motivate changes at the OS or app store level to block insecure traffic, just like browsers now enforce HTTPS. Operating systems or app stores could do more to enforce encryption standards.

TS: Now that we’re nearing the end of our interview, do you have advice for students interested in combining CS [computer science] with public interest work? And any tips for coming up with good research questions?

MW: Yes—question everything and talk to a wide range of people. The communities most impacted by surveillance are often the most vulnerable. When I worked at EFF, I collaborated with international activists and journalists, which helped me understand why privacy matters. You need those real-world perspectives to find meaningful problems. In CS, it’s easy to get caught up in performance optimization, but we should also ask: how does this help people?

TS: Before we wrap up, we usually end with a fun blog-style question. Would you be up for a quick one-minute response to something like “People would care more about cybersecurity if they knew…” or “What’s a recent cybersecurity misconception you’ve seen in the media?”

MW: Sure—one big misconception is around the app RedNote. After TikTok concerns, people feared that Chinese apps would give the Chinese government access to their data. But in our analysis, the real issue was the insecure encryption, which actually made the data vulnerable to the U.S. government, or any government where the user is located. So yes, Chinese apps may have flaws, but they also expose users to domestic surveillance due to poor encryption.

TS: That’s a fascinating point—people often fear foreign surveillance, but forget that insecure platforms also expose them to local threats. Thank you again for your time and for being willing to do this.

Read more about Mona’s work about RedNote on The Citizen Lab.

Tsion Kergo is a Princeton University junior majoring in Computer Science, pursuing minors in Machine Learning & Statistics and African-American Studies. She works at the Center for Information Technology Policy as a Student Associate, along with fellow undergrad Jason Persaud. Together they are piloting a new series called Meet the Researcher.

Leave a Reply