There’s an ongoing arms race between ad blockers and websites — more and more sites either try to sneak their ads through or force users to disable ad blockers. Most previous discussions have assumed that this is a cat-and-mouse game that will escalate indefinitely. But in a new paper, accompanied by proof-of-concept code, we challenge this claim. We believe that due to the architecture of web browsers, there’s an inherent asymmetry that favors users and ad blockers. We have devised and prototyped several ad blocking techniques that work radically differently from current ones. We don’t claim to have created an undefeatable ad blocker, but we identify an evolving combination of technical and legal factors that will determine the “end game” of the arms race.

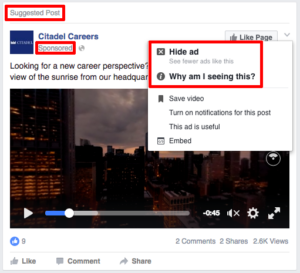

Our project began last summer when Facebook announced that it had made ads look just like regular posts, and hence impossible to block. Indeed, Adblock Plus and other mainstream ad blockers have been ineffective on Facebook ever since. But Facebook’s human users have to be able to tell ads apart because of laws against misleading advertising. So we built a tool that detects Facebook ads the same way a human would, deliberately ignoring hidden HTML markup that can be obfuscated. (Adblock Plus, on the other hand, is designed to be able to examine only the markup of web pages and not the content.) Our Chrome extension has several thousand users and continues to be effective.

Our project began last summer when Facebook announced that it had made ads look just like regular posts, and hence impossible to block. Indeed, Adblock Plus and other mainstream ad blockers have been ineffective on Facebook ever since. But Facebook’s human users have to be able to tell ads apart because of laws against misleading advertising. So we built a tool that detects Facebook ads the same way a human would, deliberately ignoring hidden HTML markup that can be obfuscated. (Adblock Plus, on the other hand, is designed to be able to examine only the markup of web pages and not the content.) Our Chrome extension has several thousand users and continues to be effective.

We’ve built on this early success. Laws against misleading advertising apply not just on Facebook, but everywhere on the web. Due to these laws and in response to public-relations pressure, the online ad industry has developed robust self-regulation that standardizes the disclosure of ads across the web. Once again, ad blockers can exploit this, and that’s what our perceptual ad blocker does. [1]

The second prong of an ad blocking strategy is to deal with websites that try to detect (and in turn block) ad blockers. To do this, we introduce the idea of stealth. The only way that a script on a web page can “see” what’s drawn on the screen is to ask the user’s browser to describe it. But ad blocking extensions can control the browser! Not perfectly, but well enough to get the browser to convincingly lie to the web page script about the very existence of the ad blocker. Our proof-of-concept stealthy ad blocker successfully blocked ads and hid its existence on all 50 websites we looked at that are known to deploy anti-adblocking scripts. Finally, we have also investigated ways to detect and block the ad blocking detection scripts themselves. We found that this is feasible but cumbersome; at any rate, it is unnecessary as long as stealthy ad blocking is successful.

The details of all these techniques get extremely messy, and we encourage the interested reader to check out the paper. While some of the details may change, we’re confident of our long-term assessment. That’s because our techniques are all based on sound computer security principles and because we’ve devised a state diagram that describes the possible actions of websites and ad blockers, bringing much-needed clarity to the analysis and helping ensure that there won’t be completely new techniques coming out of left field in the future.

There’s a final wrinkle: the publishing and advertising industries have put forth a number of creative reasons to argue that ad blockers violate the law, and indeed Adblock Plus has been sued several times (without success so far). We carefully analyzed four bodies of law that may support such legal claims, and conclude that the law does not stand in the way of deploying sophisticated ad blocking techniques. [2] That said, we acknowledge that the ethics of ad blocking are far from clear cut. Our research is about what can be done and not what should be done; we look forward to participating in the ethical debate.

This post was edited to update the link to the paper to the arXiv version (original paper link).

[1] To avoid taking sides on the ethics of ad blocking, we have deliberately stopped short of making our proof-of-concept tool fully functional — it is configured to detect ads but not actually block them.

[2] One of the authors is cyberlaw expert Jonathan Mayer.

Leave a Reply