Authored by: Sofia Avila, Yasemin Savas, and Matthew Salganik

U.S. adults in 2019 spent more than 6 hours a day using digital media. In 2021, 1/3 of American adults reported being constantly online. Despite the extensive time spent on social media, users often overlook how these platforms shape their attention, habits, and mood. Social media and its effects have been extensively discussed in academia. Studies have linked social media use with anxiety, depression, and eating disorders. Yet, some scholars emphasize that social media can be a helpful tool under some certain specific situations such as stress and depression, suicide prevention, and may provide support for some marginalized groups, such as LGBTQ+ youth. And others have argued that social media use is not really associated with mental well-being whatsoever.

This semester, our Princeton undergraduate social networks class explored the possibilities of changing social media habits to better understand the process of doing research. All 45 students in our class designed and conducted a ten-day intervention aimed at changing their social media habits and pre-registered a hypothesis for how the intervention would impact their behavior and mood. Here, we summarize what students tried and what they learned. We also include the materials if you are interested in self-experimenting with your own social media use, either on your own or with a class you teach.

Student Interventions

Our class included a variety of students from different years and majors. Each student developed their own interventions, formulated hypotheses about possible effects, identified their motivation, and outlined outcomes to track during a 10-day period. They reflected on their own experiment through weekly assignments and discussions with their peers.

The interventions students developed can be categorized into three main groups:

Targeted limitation (approximately 60%): Students in this group limited their social media use. Some tracked their daily screen time (e.g., no use after 30 minutes daily), and some others restricted use after a specific time (e.g., no use of TikTok after 8 pm).

Elimination (approximately 38%): Students in this group decided to entirely abstain from either (1) a specific app or (2) the whole social media altogether. Some students replaced time spent on these platforms with finishing novels, journaling, or actively spending more time with friends.

Targeted increase (approximately 2%): Only one student decided to do a targeted increase. The only intervention in this category was increasing direct messaging to 3+ friends daily.

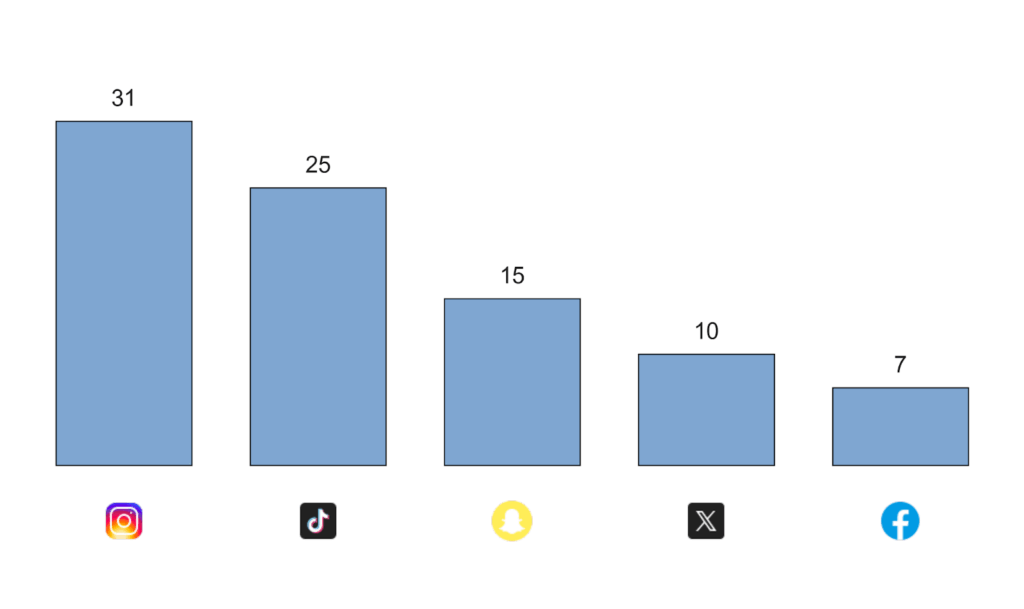

Figure 1: Top 5 most targeted platforms in social media interventions. One student may be on multiple platforms.

What Happened When Students Changed Their Social Media Habits?

The experiences of students varied widely. Many students reported positive effects, particularly for outcomes related to time management and academic focus (e.g., completing schoolwork, sleeping more consistently). Interestingly, several also found that their social media use became more purposeful. Instead of browsing passively, they used their time to respond to direct messages or engage with content they found genuinely meaningful.

For others, the outcomes of the experiment were more muted. Some students did not observe any changes in the outcomes they were measuring and a few even noted the intervention negatively impacted them in undesirable ways. For example, several students who limited or eliminated social media use mentioned feeling some loneliness or “FOMO”, especially when they missed messages from friends or weren’t part of conversations happening online.

Why did some students see the outcomes they hoped for, while others did not? Broadly, our observations point to three practical recommendations:

Design broad but balanced interventions

Many of the students who did not detect substantive changes in outcomes like sleep, time management, and mood had interventions that may have been too narrow. The most common cases were interventions that only applied to one or two apps such as TikTok and Snapchat. In practice, this resulted in substitution: when one app was removed or restricted, another quickly filled its place. As a result, these students may have changed the way they use social media but not necessarily reduced their time spent on it – something many of these students explicitly sought to reduce.

Yet, just as some interventions may have been too narrow, others may have been too extreme. Interventions that fully eliminate the use of some or all apps may not only be harder to adhere to but also prevent access to the functions of social media students find valuable. For example, one student – Anna Faulstich – reflected on the “positive role” these platforms can play in her life, helping her “stay connected to cultural trends, current events, and giving [her] a quick mental break.”

Without them, she said, “I sometimes felt a little out of the loop or missed that light, entertaining content I usually enjoy.”

Students who reduced but did not eliminate these apps retained the ability to stay in touch with friends from high school or family members they rarely see, without spending too much time scrolling through more addictive or impersonal content on their feeds. Overall, we find that interventions that cut across apps and devices without fully cutting out their use, may be most conducive to desirable and sustainable behavioral changes and positive outcomes.

Use friction to disrupt habits

Another factor that may have attenuated the effects of the self-experiment was imperfect adherence to the treatment. Here, we found that the students who employed some kind of commitment device were more likely to stick with the treatment. Examples included using new gadgets that allow you to convert smartphones into “brick” phones or installing apps that introduce a deliberate delay before allowing access to distracting apps. These forms of interruption seemed to help reduce automatic engagement and foster greater intentionality. In contrast, students who adopted strategies that were easy to override or “learn” were less likely to observe behavioral changes. The most common example was using Apple’s screen time limit feature. The tool notified students when they’d used their phones for more than the allotted time, but did not prevent them from continuing use. The most effective strategies, then, were those that introduced meaningful friction between the user and the app, making mindless use more difficult.

Set feasible and clear outcomes

Lastly, some students may not have perceived that their self-experiment was effective because of the kinds of outcomes they focused on. For example, students who focused on variables such as self-esteem or loneliness often reported little measurable change. One potential reason is that these outcomes are shaped by a range of factors beyond social media use and tend to vary from day to day, making short-term patterns difficult to detect. Additionally, even if social media is the main driver of low self-esteem or loneliness among some students, meaningful shifts may require longer interventions than what we did for class. Conversely, outcomes like the amount of time students spent on homework or how well they slept may be more responsive to short-term interventions and are easier to measure.

What happened when the experiment ended?

At the end of the experiment, many students expressed a strong desire to maintain their intervention or, at the very least, continue being more intentional about how they used social media. Yet relatively few were able to sustain the changes they had made. In reflecting on why that was, some suggested it was due to a kind of “overcompensation” after their intervention. As one student, Casara Croswell, explained:

“I spent more time on TikTok and Instagram compared to before the treatment was given. I think this is because by restricting myself to only an hour each day I grew to miss spending time on the platform.”

Other students often pointed to the difficulty of maintaining new habits in an environment where nothing else had changed. Friends continued to message on Instagram or Snapchat, important updates were still shared online, and the apps themselves remained just as accessible and attention-grabbing as before. This highlighted how difficult it can be to change behavior in isolation. It’s perhaps for this reason that some structural approaches—like phone restrictions in schools or national-level policies aimed at platform regulation—have started to take shape.

Still, self-experimentation can be a useful way to gain insight into your habits, experiment with meaningful changes, and reflect on the role these platforms play in your daily life.

Jane Kuehl, for example, reflected that “the way I use social media, especially TikTok, has changed drastically. Before the experiment, I used to sit on TikTok and waste away hours of my day…However, after the experiment, I was way more intentional with the time I spent on TikTok…I am glad I did the experiment because it helped me rethink my use of TikTok and other social media platforms.” Others emphasized how the activity encouraged broader reflection.

As Kristof Kovacs put it, “I liked this activity as I feel it reflected on my social media habits and on what is good and not good for me. I would encourage students more to try out radical changes as I think it can change their perception of social media

usage a lot.”

Try It Yourself

If you’re curious about your own relationship with social media or interested in learning from self-experimentation, you can follow a version of the activity we used in class.

We’ve included links to a slightly adapted version of the materials we used at Princeton:

And, for a bit more information about the class, see:

About the Authors:

Sofia Avila is a Ph.D. student in Princeton Sociology and Social Policy. She received her B.S. in Symbolic Systems with a concentration in Computational Social Science and a minor in Data Science from Stanford University. Her undergraduate thesis used administrative data to determine the effects of worksite immigration raids on the academic performance of Hispanic children in nearby communities.

Yasemin Savas is a Ph.D. student in Sociology at Princeton University studying the social impacts of climate and environmental change. Broadly speaking, her work focuses on how climate shocks shape migration, household decision-making, and inequality, with current projects in sub-Saharan Africa. Methodologically, she employs quantitative and computational social science approaches.

Matthew Salganik is Professor of Sociology at Princeton University. He is also affiliated with several of Princeton’s interdisciplinary research centers including the Office of Population Research, the Center for Statistics and Machine Learning, and the Center for Information Technology Poliyc. His research interests include social networks and computational social science. He is the author of Bit by Bit: Social Research in the Digital Age

Leave a Reply