How mail-in ballot envelopes are handled by local election officials can make a huge difference in the cost of recounts and can also affect the security of elections against one form of voting fraud.

- Part 1 of this series: Sort the mail-in ballot envelopes, or don’t? (and why it matters)

- Part 2: Best practices for sorting mail-in ballots

- Part 3: Expensive and ineffective recounts in Los Angeles County

- Part 4: Willful disregard of voter intent in Los Angeles

Counties that count thousands or millions of mail-in (or dropbox) ballots can do it two ways:

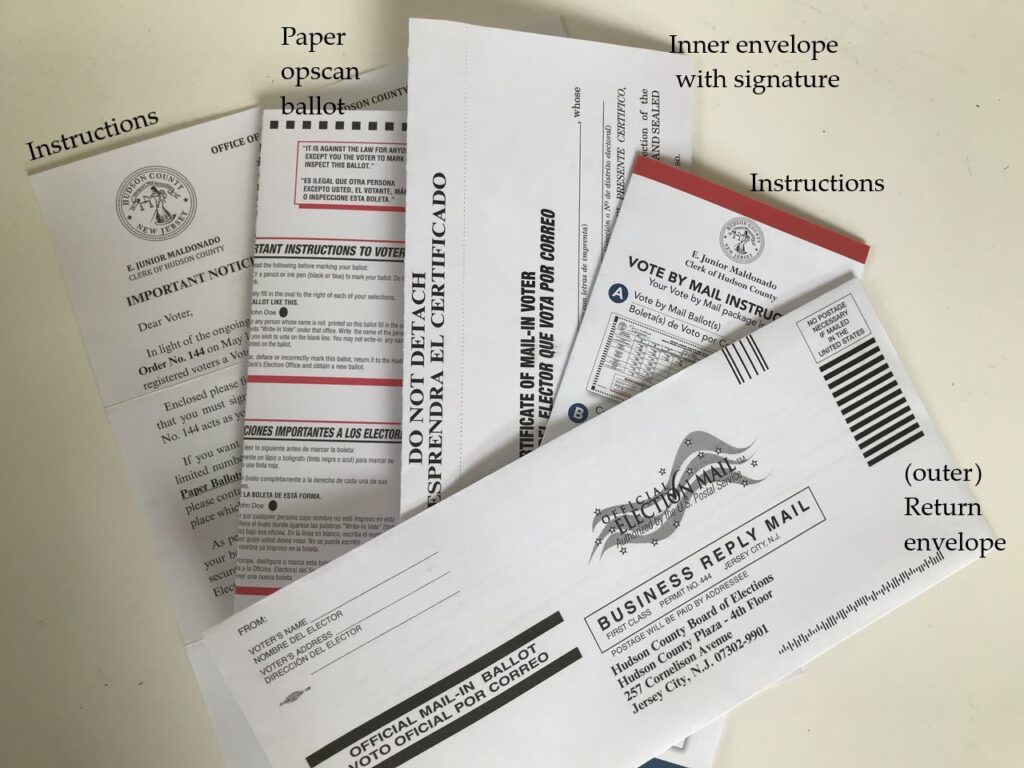

Sort-then-scan: Sort the ballot envelopes by precinct-number, using the voter information and signature on the outside of the envelope; open the envelopes and unfold/flatten the paper ballots within; then scan a stack of all-the-same-precinct ballots.

Scan-then-sort: Take a big batch of unsorted ballot envelopes from various precincts in the jurisdiction; open all the envelopes in the batch and unfold/flatten the paper ballots; then scan a stack of various-precinct ballots. Because each ballot has its precinct-number printed on it as a barcode, the computers will be able to allocate the votes to the right precincts.

In each method, the voter’s name, address, voter-registration-number, and signature is on the envelope; before opening the envelope, look this up in the poll-book database, to check that the voter hasn’t already voted, and mark in the database that they have now voted.

Scan-then-sort has three problems: (1) opportunity for cheating (2) grossly expensive recounts (3) extra expense in ballot printing.

First problem with scan-then-sort: opportunity for cheating: a voter could try to cheat in an election by voting in a different precinct. Suppose you live in the city of Townville, but you’d really rather vote in the mayoral election of Burgton (another town in the same county). Or suppose your county is split between two Congressional districts: your district is a landslide, hardly worth voting in, but the other is a swing district and you’d rather vote there. Just make a copy of the Burgton ballot, (illegitimately) vote in those contests, put it in your Townville envelope, and mail it in. By the time any computer or person actually looks at your paper ballot, it will have been completely separated from your envelope. (Don’t try to cheat this way, it’s illegal!)

I’ve talked to three experienced election administrators about this. Two-and-a-half of them are sure this attack couldn’t work, because your fake copy of the Burgton ballot would be low-quality, or would be on the wrong kind of paper, and the election workers would notice that even as they’re opening the envelope. I’m not so sure, especially in these days when everyone has access to high-resolution PDF printing. And I’ve talked to one person who says this was a large-scale practice where she once lived: operatives would raid the trash cans in apartment-complex mailrooms for unvoted ballots to use in exactly this way.

Election administrators also tell me, “there would be more ballots reported for Burgton than envelopes, and the discrepancy would be noticed.” But even if it’s noticed, that doesn’t mean it can be corrected! By the time the ballots have been separated from their identifying information, it’s too late; the only correction would be a do-over election.

On the other hand, this attack (totally illegal, don’t even think of doing it) would not succeed with the sort-then-scan method. In that method, what you feed through the scanner is (supposed to be) a stack of all-one-precinct ballots, each encoded with its precinct-ID barcode. Any ballot with the wrong precinct-ID will be detected by the scanner. In fact, in well-organized election offices this is caught as soon as the envelope is opened; see my note below about Montgomery County, MD.

Second problem with scan-then-sort: recounts. Suppose a candidate for Mayor of Townville demands a recount of the mayor’s race, as entitled by state law. Remember, an important purpose of a recount is to make sure the computers didn’t get anything wrong, so it’s important to look at the actual paper ballots. Among the 1 million ballots in the whole county, how do you find the 30,000 paper ballots from the 60 precincts of the Townville? With the sort-then-scan method, it’s easy: there are 60 distinct and identifiable batches of ballots, easy to find in the county vault, and those are the ballots to recount. But with scan-then-sort, those ballots will be scattered among all the batches, and it will be extremely expensive to find them.

This recount problem is not merely hypothetical. In 2020 in Los Angeles County, the City of Long Beach had a tax-rate referendum on which the voting machines reported 49,676 “yes” votes and 49,660 “no”—a 16-vote margin of victory. A citizens’ group asked for a recount of the paper ballots in the City of Long Beach’s tax-rate referendum. By California law they were entitled to a recount provided they paid for it; and according to the guidelines published by LA County this should have cost approximately $20,000 (about 20 cents per ballot to pay the 4-person teams that would tally and recount). But the LA County election officials then told them that they’d first have to pay about $187,000 just to sort the 2.1 million LA County ballots and find the 100,000 Long Beach ballots within them—plus the cost of recounting them. [see note below] In Los Angeles County, 54% of the ballots were mail-in ballots, the rest were vote-center ballots. None of these had been physically sorted by precinct. So, scan-then-sort raised the price of a recount by about a factor of 10.

In Hays County Texas, a candidate asking for a recount of a 2022 countywide District Attorney race had to pay about three times as much for a hand recount (about $30,000 instead of $10,000), because of the extra time it took for the recount teams just to sort each bag of ballots by precinct before starting the actual count. Most of these ballots were cast in vote centers. [see note below]

Third problem with scan-then-sort: Most jurisdictions require election officials to account for every vote cast by the precinct in which the voter is registered. With scan-then-sort, that requires every precinct to have its own ballot-style number printed (barcoded) onto the ballot. This proliferation of ballot styles causes extra expense in printing, extra work in logic-and-accuracy testing, extra work in logistics. In contrast, with sort-then-scan, many precincts can share the same ballot-style number, as long as they all have the same set of contests and candidates—because the voter information on the outside of the envelope is enough to sort by precinct.

Conclusion. The Latin phrase from 1209, “Caedite eos. Novit enim Dominus qui sunt eius”, roughly translated as “Kill them all and let God sort them out,” expresses pretty well the scan-then-sort method, which we could write in Latin as Numerate eos. Novit enim machina quo irent (count them all, the computer knows where they go). Either way, it was a bad idea in 1209 and it’s a bad idea now.

Fortunately, for mail-in ballots there’s a clear solution. Some high-population counties use sorting equipment to sort ballot envelopes into batches by precinct, before opening them. So the sort-then-scan method can be done in a cost-effective way, and in many jurisdictions that’s what they do. In other jurisdictions they do sort-then-scan without even needing high-tech equipment.

But in LA County and in Hays County, many of the unsorted ballots were from in-person vote centers: each voter can use any vote center in the county, they are supplied with the appropriate ballot style (marked by precinct-number barcode), and the machines sort them out electronically. With unsorted vote-center ballots, recounts are difficult, and I’m not sure what the best solution is.

Part 2: How to sort mail-in ballots

Notes

- Long Beach, California: The description above of recount costs comes from the Plaintiffs’ brief in Long Beach Reform Coalition v. Dean C. Logan, 2021.

- Hays County, Texas: The information about sorting and recount effort comes from an interview with Laura Nunn, who was employed by Hays County to work in one of the recount teams. The “upwards of $40,000” referred to in the CBS News article included extra photocopying, requested by the candidate, that was not part of the recount proper.

- Montgomery County, Maryland: Montgomery County uses a high-speed envelope scanner/sorter to sort mail-in ballots before opening the envelopes. My next article will describe how they do it.

Leave a Reply