Based on preliminary reports published by the team of experts that New Hampshire engaged to examine an election discrepancy, it appears that a buildup of dust in the read heads of optical-scan voting machines (possibly over several years of use) can cause paper-fold lines in absentee ballots to be interpreted as votes. In a local contest in one town, preliminary reports suggest this caused four Republican candidates for State Representative to be deprived of about 300 votes each. That didn’t change the outcome of the election–the Republicans won anyway–but it shows that New Hampshire (and other states) may need to maintain the accuracy of their optical-scan voting machines by paying attention to three issues:

- Routine risk-limiting audits to detect inaccuracies if/when they occur.

- Clean the dust out of optical-scan read heads regularly; pay attention to the calibration of the optical-scan machines.

- Make sure that the machines that automatically fold absentee ballots (before mailing them to voters) don’t put the fold lines over vote-target ovals. (Same for election workers who fold ballots by hand.)

Everything I write in this series will be based on public information, from the State of New Hampshire, the Town of Windham, and the tweets of the WindhamNHAuditors.

In the November 3, 2020 general election in Windham, New Hampshire, the race for State Representative was very close–24 votes difference–so one candidate asked for a recount. The recount showed that she lost by hundreds of votes–not just 24. The hand recount of the optical-scan paper ballots disagreed with the numbers claimed by the optical-scan voting machines to an extent that was shocking. The citizens of New Hampshire demanded to know: were the op-scan machines hacked? Were the machines misconfigured and reading marks from the wrong place in the paper? Did creases in absentee ballots cause the op-scan machines to misread votes? Was the recount itself erroneous?

The Secretary of State said that there was no provision in New Hampshire law that permitted him to do a re-recount, or to examine the voting machines for hacking. So a Republican legislator introduced a bill for a forensic audit to find out what had happened. That bill passed the legislature unanimously:

… [T]his act authorizes and directs an audit of the ballot counting machines and their memory cards and the hand tabulations of ballots regarding the general election on November 3, 2020 in Windham, New Hampshire of Rockingham County district 7 house of representatives for the purpose of determining the accuracy of the ballot counting devices, the process of hand tallying, and the process of vote tabulation and certification of races.

A forensic election audit team shall be formed to complete the audit described in section 3 and it shall be comprised of: one person designated by town of Windham, one person designated jointly by the … secretary of state and attorney general, [and one person to be chosen by those two auditors]. … The results of the audit shall not alter the official results of the Rockingham County district 7 house of representatives race as determined by the ruling of the ballot law commission on November 25, 2020, upholding the recount of that race.

Governor Sununu signed bill SB43 into law on April 12, 2021. On April 26 the town of Windham chose Mark Lindeman of the Verified Voting Foundation as its auditor, and the Attorney General (upon the advice of the Secretary of State) chose Harri Hursti, a well known expert on the cybersecurity of voting machines and bank ATM machines. Those two then selected Philip Stark, of the University of California at Berkeley, as the third auditor.

This is truly a “dream team” of experts. They know what they’re doing, they’re experienced with election audits and the forensic examination of voting machines, and they know how elections work. New Hampshire could not have found anyone better prepared to get to the heart of the matter.

What happened in Windham

The town of Windham has a single polling place, in which 10,006 ballots were cast: 6697 in-person and 2949 absentee scanned by machine, and 80 absentee counted by hand (because overseas “UOCAVA” ballots are in a different format that the machines didn’t accept).

In New Hampshire, absentee ballots are processed in the polling place, on election day. That is, there’s a preprinted voter list. When registered voter shows up to vote in person, their name is found on the list, and crossed out. An absentee ballot envelope is processed by checking the voter’s name (from the envelope) against the same preprinted voter list, and crossing it out; then the absentee ballot is removed from the envelope, and scanned into the same voting machines that are used for in-person ballots.

That procedure is a way of checking that the same person doesn’t vote absentee more than once, or doesn’t vote both absentee and in person: their name appears only once on the list, and can be crossed off only once.

In Windham on November 3rd, there were four optical-scan voting machines, Global Election Systems model “AccuVote OS”, purchased in 1998 and 2000. The 6697 in-person and 2949 scannable absentee ballots were fed into those four machines during the day. That’s something like one ballot every 10 or 15 seconds into each machine, all day long!

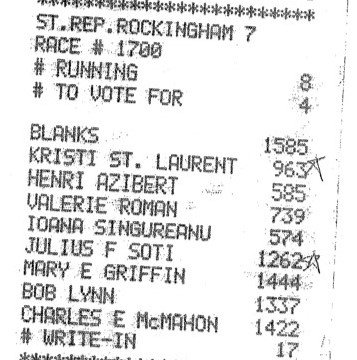

At the close of the polls, each machine printed its result out onto a “results tape”–thermal cash-register paper listing how many votes each candidate got. There were four “results tapes”, one per machine; here’s a small portion of just one of them, for the State-Rep contest:

In this race, there were 8 candidates running for 4 seats, and every voter got to vote for four out of 8.

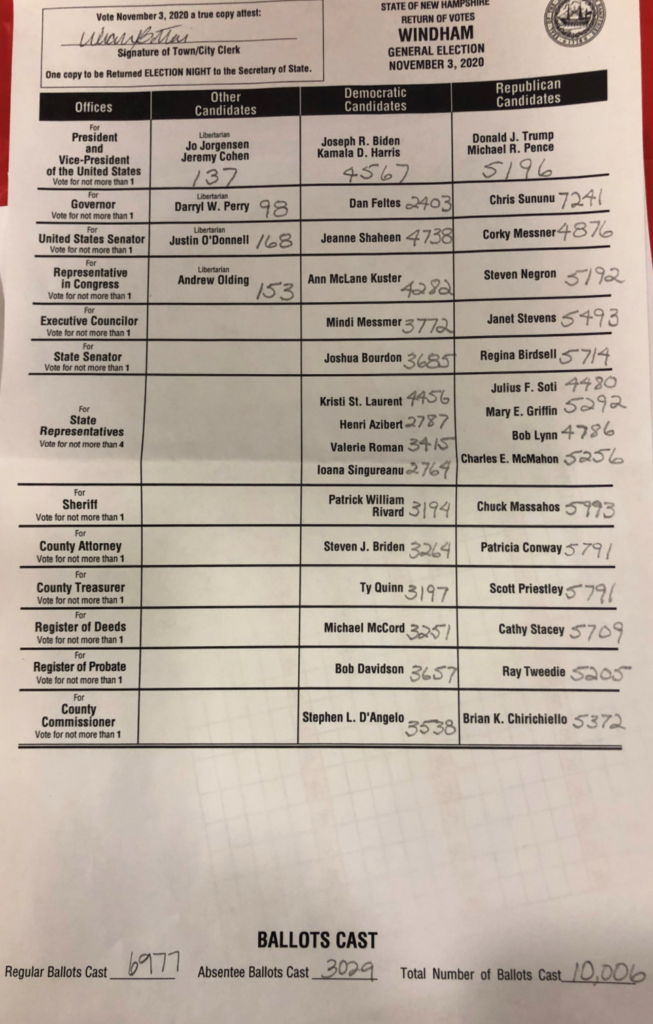

Election administrators aggregated the four voting-machine results tapes by hand (along with the 80 hand-counted ballots) onto a paper worksheet to produce an official “Return of Votes” form, signed by the Town Clerk.

In the race for State Rep, in 5th place out of 4 seats, Kristi St. Laurent was only 24 votes behind the 4th-place candidate Julius Soti. So she asked for a recount. By state law, those are done by hand, by the office of the Secretary of State, in Concord (the state capital).

The results of the recount were:

| Original | Recount | Diff | |

| Kristi St. Laurent (D) | 4,456 | 4,357 | -99 |

| Henri Azibert (D) | 2,787 | 2,808 | +21 |

| Valerie Roman (D) | 3,415 | 3,443 | +28 |

| Ioana Singureanu (D) | 2,764 | 2,782 | +18 |

| Julius Soti (R) | 4,480 | 4,777 | +297 |

| Mary Griffin (R) | 5,292 | 5,591 | +299 |

| Bob Lynn (R) | 4,786 | 5,089 | +303 |

| Charles McMahon (R) | 5,256 | 5,554 | +298 |

| TOTAL | 33,236 | 34,401 | +1,165 |

As you can see, something is grossly wrong–either with the machine counts, or the hand counts, or both. The people of New Hampshire, and their legislators, wanted to understand how this happened–and how to prevent it in the future.

The audit team looked at,

- the voting machines (and their ballot programming, and their performance under the kind of heavy usage they saw last November);

- the paper ballots (and associated records), as preserved by the Secretary of State from the November recount

- and the context, learning from election administrators in Windham and other New Hampshire towns about polling-place procedures.

What caused the discrepancy

The audit team has not yet written their official report, so everything I’ll describe here is only their preliminary findings as described in their tweets.

The auditors supervised a careful recount by teams of 5 people (caller, checker, 2 tallyers, flagger). Members of each team included Democrats, Republicans, and independents. The hand count was within 0.05% of the official state recount, for every State Rep candidate (the State did not recount the races for President, Senator, etc.). So, basically, the official state recount was right, the voting machines were wrong; why?

There is zero evidence that the voting machines were hacked. Forensic exams show that the software in these machine matches the reference machine provided by the Secretary of State’s office (the audit team will continue to examine that software to make sure the SoS’s copy is right), and there was nothing unexpected in the memory cards.

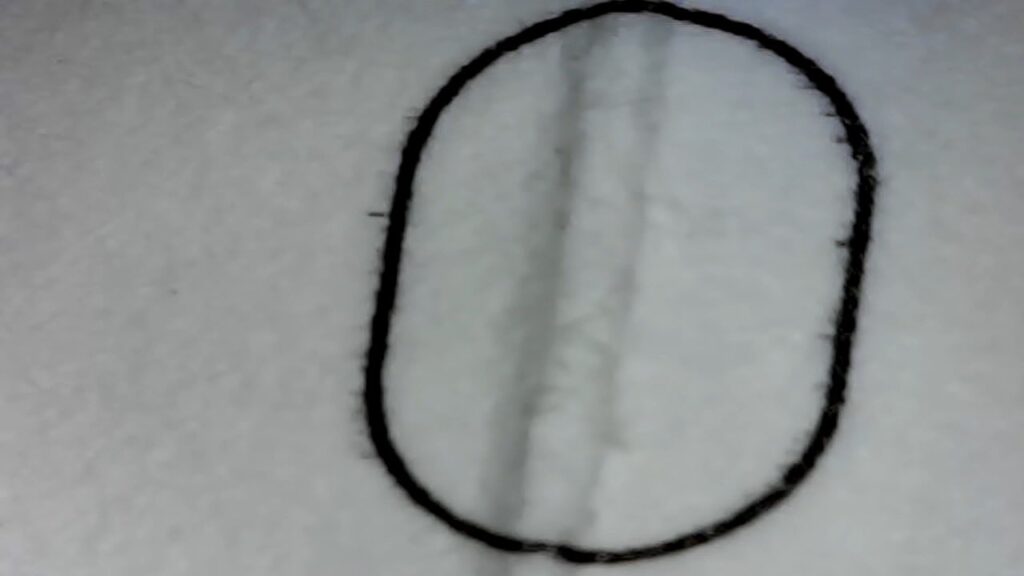

Folds in ballot papers. Ballot papers marked by voters in the polling place were (generally) not folded. Absentee ballots have identical printing; they were folded in thirds before they were mailed to the voters; marked by the voters at home, refolded and mailed back to the Town Clerk, and then (on election day) scanned through the same voting machines as the in-the-polling-place ballots.

What happens if a fold goes through one of the “vote targets” (the ovals that voters are supposed to fill in with a pen to indicate their choice)? The voting machine is not supposed to interpret a fold as a mark. But the audit team found that in many cases, a fold would be read as a mark:

The fold lines in absentee ballots weren’t always in exactly the same place, but in hundreds of ballots they crossed through the target for Democratic candidate Kristi St. Laurent. Now, consider what happens if an voter marks all 4 Republican candidates (and none of the 4 Democratic candidates), by blackening their ovals with a pen. If the optical-scanner also interprets the fold line through one Democratic candidate as a mark, then the machine “thinks” there are 5 votes in a vote-for-4 contest; and that’s an overvote, so all of those votes won’t be counted.

Many voters voted straight-party: all R, or all D. The effect of this was that hundreds of votes for the Republican candidates were not counted. An all-Democratic vote, with a fold line through a blackened target, would not be affected.

In the recount, with humans looking at the votes, the votes were counted accurately. Humans are not likely to interpret a fold line as a vote! So the official Windham results (after the recount) are trustworthy.

But many towns in New Hampshire use the same AccuVote optical-scan voting machines. We can legitimately wonder whether some elections in other towns (that were not recounted by hand) got the wrong result. I’ll discuss that question in my next post.

In my next article I’ll examine:

- What do the national voting-machine standards say about how voting machines should distinguish fold-lines from intentional vote-marks?

- Could a build-up of dust make the voting machine more likely to misinterpret folds as marks?

- What do election administrators in other states do to avoid this problem?

- Should New Hampshire throw away its voting machines and buy new ones, or throw away its voting machines and count votes by hand? Or are there measures they could take to use these same machines in a trustworthy way?

- What series of circumstances led to this problem in Windham 2020, and how could those corrective measures prevent anything like this from happening again?

- Could improved technology in optical-scan voting machines be less susceptible to this problem?

Leave a Reply