Preliminary unofficial election results posted at 4am after the November 3rd 2020 election, by election administrators in Antrim County Michigan, were incorrect by thousands of votes–in the Presidential race and in local races. Within days, Antrim County election administrators corrected the error, as confirmed by a full hand recount of the ballots, but everyone wondered: what went wrong? Were the voting machines hacked?

The Michigan Secretary of State and the Michigan Attorney General commissioned an expert to conduct a forensic examination. Fortunately for Michigan, one of the world’s leading experts on voting machines and election cybersecurity is a professor at the University of Michigan: J. Alex Halderman. Professor Halderman submitted his report to the State on March 26, 2021 and the State has released the report.

Analysis of the Antrim County, Michigan

November 2020 Election Incident

J. Alex Halderman

March 26, 2021

And here’s what Professor Halderman found: “In October, Antrim changed three ballot designs to correct local contests after the initial designs had already been loaded onto the memory cards that configure the ballot scanners. … [A]ll memory cards should have been updated following the changes. Antrim used the new designs in its election management system and updated the memory cards for one affected township, but it did not update the memory cards for any other scanners.”

Here’s what that means: Optical-scan voting machines don’t (generally) read the text of the candidates’ names, they look for an oval filled in at a specific position on the page. The Ballot Definition File tells the voting machine what name corresponds to what position. And also informs the election-management system (EMS) that runs on the county’s election management computers how to interpret the memory cards that transfer results from the voting machines to the central computers.

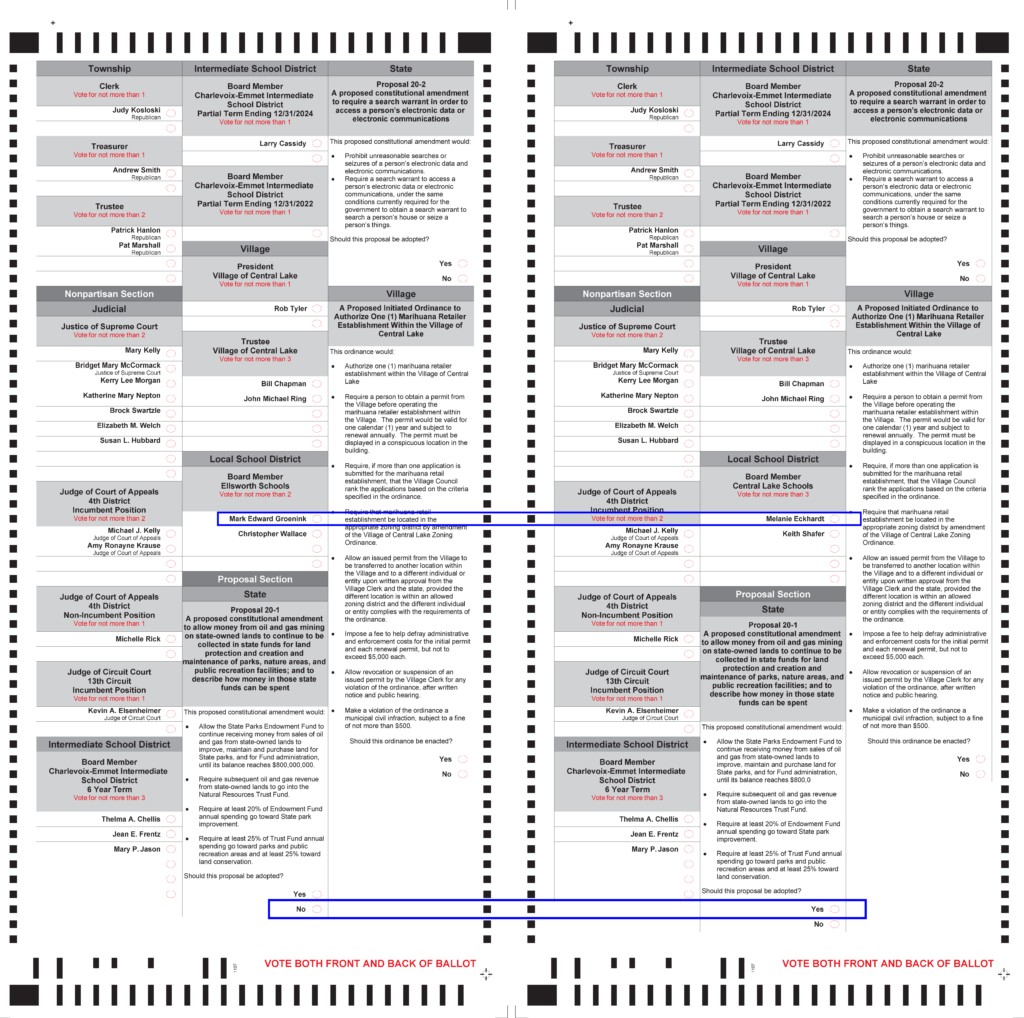

Shown here at left is the original ballot layout, and at right is the new ballot layout. I have added the blue rectangles to explain Professor Halderman’s report.

Now, if the voting machine is loaded with a memory card with the ballot definition at left, but fed ballots in the format at right, what will happen?

A voter’s mark next to the name “Melanie Eckhart” will be interpreted as a vote for “Mark Edward Groenink”. That is, in the first blue rectangle, you can see that the oval at that same ballot position is interpreted differently, in the two different ballot layouts.

A voter’s mark next to “Yes” in Proposal 20-1 will be interpreted as “No” (as you can see by looking at the second blue rectangle).

We’d expect that problem with any bubble-ballot voting system (though there are ways of preventing it, see below). But the Dominion’s results-file format makes the problem far worse.

In Dominion’s file format for storing the results, every subsequent oval on the paper is given a sequential ID number, cumulative across all ballot styles used in the county. Now look at the figure above, just below the first blue rectangle. You’ll see that in the original “Local School District” race (at left) there are two write-in bubbles, but in the revised “Local School District” race (at right), there are three write-in bubbles. That means the ID number of every subsequent bubble, on this ballot and in all the ballot styles that come after it in this county, the ID numbers will be off by one. Figure 2 of the report illustrates:

Within three days, Antrim County officials had basically figured out what went wrong, and corrected most of the errors before publishing and certifying official election results on November 6th. By November 21, Antrim County had corrected almost all of the errors in its official restatement of its election results.

How do we know that the original results were wrong and the new results are right? That is, how do we know that the “corrected” results are true, and not fraudulent? We have two ways of knowing:

- Hand-marked paper ballots speak for themselves. The contest for President of the U.S. was recounted by hand in Antrim County. Those results–from what bipartisan workers and witnesses could see with their own eyes–matched the results from scanning the paper ballots using the ballot-definition file that matches the layout of the paper ballot.

- A careful forensic examination by a qualified expert can explain what happened, and that is why Professor Halderman’s report is so valuable–it explains things step by step.

But not every contest was recounted by hand. The expert analysis finds a few contests where the reported vote totals are still incorrect; and in one of those contests (a marijuana ballot question) the outcome of the election was affected.

In the court case of Bailey v. Antrim, plaintiffs had submitted a report (December 13, 2020) from one Russell J. Ramsland making many claims about the Dominion voting machines and their use in Antrim County: adjudication, error rates, log entries, software updates, Venezuela. Section 5 of Professor Halderman’s report addresses all of these claims and finds them unsupported by the evidence.

What can we learn from all of this?

- Although the unofficial reports posted at 4am on November 4th showed Joseph R. Biden getting more votes in Antrim County than Donald J. Trump, the results posted November 6th show correctly that, in Antrim County, Mr. Trump got more votes.

- Regarding the presidential contest, election administrators figured this out for themselves without needing any experts.

- In other contests, where no recount was done, most of the errors got corrected, but not all.

- There is no evidence that Dominion voting systems used in Antrim County were hacked.

And what can we learn about election administration in general?

- Hand marked paper ballots are extremely useful as a source of “ground truth”.

- If the ballot definition doesn’t match the paper ballot, results reported by the optical-scan voting machine can be nonsense. This has happened before–see my report describing a 2011 incident in New Jersey.

- “Unforced error:” Dominion’s election-management system (EMS) software doesn’t check candidate names. The EMS computer has a file mapping ballot-position numbers to candidate names; and the memory card uploaded from the voting machine has its own file mapping ballot-position numbers to candidate names. If only the EMS software had checked that these files agreed, then the problem would have been detected on election night, during the upload process.

- Even without that built-in checking, to catch mistakes like this before the election, officials should do the kind of end-to-end pre-election logic-and-accuracy testing described in Professor Halderman’s report.

- Risk-Limiting Audits (RLAs) could have detected and corrected this error, if they had been used systematically in the State of Michigan. RLAs are good protection not only against hacking, but also against mistakes and bugs.

Leave a Reply