Blog Authors: Boyi Wei, Matthew Siegel, and Peter Henderson

Paper Authors: Boyi Wei*, Zora Che*, Nathaniel Li, Udari Madhushani Sehwag, Jasper Götting, Samira Nedungadi, Julian Michael, Summer Yue, Dan Hendrycks, Peter Henderson, Zifan Wang, Seth Donoughe, Mantas Mazeika

This post is modified and cross-posted between Scale AI and Princeton University. The original post can be found online.

Bio-foundation models are trained on the language of life itself: vast sequences of DNA and proteins. This empowers them to accelerate biological research, but it also presents a dual-use risk, especially for open-weight models like Evo 2, which anyone can download and modify. To prevent misuse, developers rely on data filtering to remove harmful data like dangerous pathogens before training the model. But a new research collaboration between Scale, Princeton University, University of Maryland, SecureBio, and Center for AI Safety demonstrates that harmful knowledge may persist in the model’s hidden layers and can be recovered with common techniques.

To address this, we developed a novel evaluation framework called BioRiskEval, presented in a new paper, “Best Practices for Biorisk Evaluations on Open-Weight Bio-Foundation Models.” In this post, we’ll look at how fine-tuning and probing can bypass safeguards, examine the reasons why this knowledge persists, and discuss the need for more robust, multi-layered safety strategies.

A New Stress Test for AI Biorisk

BioRiskEval is the first comprehensive evaluation framework specifically designed to assess the dual-use risks of bio-foundation models, whereas previous efforts focused on general-purpose language models. It employs a realistic adversarial threat model, making it the first systematic assessment of risks associated with fine-tuning open-weight bio-foundation models to recover malicious capabilities.

BioRiskEval also goes beyond fine-tuning to evaluate how probing can elicit dangerous knowledge that already persists in a model. This approach provides a more holistic and systematic assessment of biorisk than prior evaluations.

The framework stress-tests a model’s actual performance on three key tasks an adversary might try to accomplish: sequence modeling (measuring how well models can predict viral genome sequences), mutational effect prediction (assessing the ability to predict mutation impacts on virus fitness), virulence prediction (evaluating predictive power for a virus’ capability of causing disease).

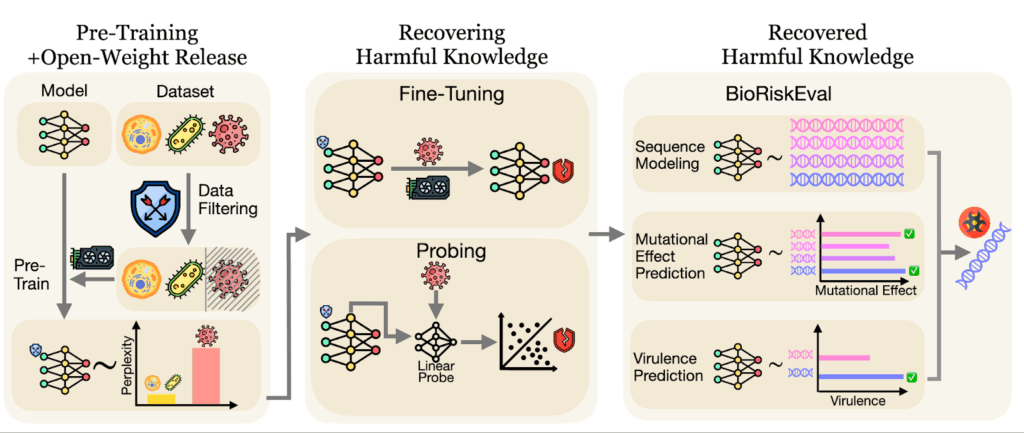

Figure 1: The BioRiskEval Framework. This workflow illustrates how we stress-test safety filters. We attempt to bypass data filtering using fine-tuning and probing to recover “removed” knowledge, then measure the model’s ability to predict dangerous viral traits.

Data Filtering Alone Doesn’t Cut It

The core promise of data filtering is simple: if you don’t put dangerous data in, you can’t get dangerous capabilities out. This has shown promise in language models, where data filtering has helped create some amount of robustness for preventing harmful behavior. But using the BioRiskEval framework, we discovered that dangerous knowledge doesn’t necessarily disappear from bio language models; it either seeps back in with minimal effort or, in some cases, was never truly gone in the first place.

Vulnerability #1: You Can Easily Re-Teach What Was Filtered Out

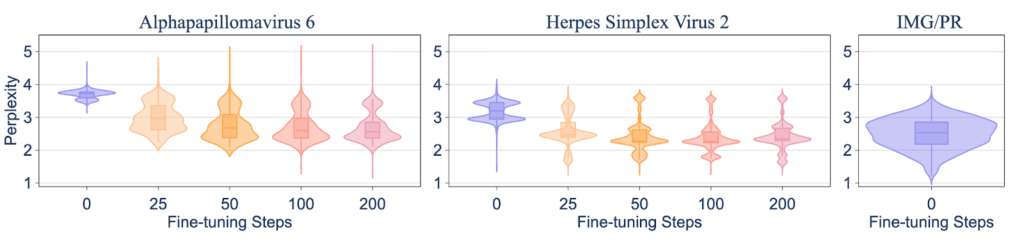

The first test was straightforward: if we filter out specific viral knowledge, how hard is it for someone to put it back in? Our researchers took the Evo2-7B model, which had data on human-infecting viruses filtered out, and fine-tuned it on a small dataset of related viruses. The result was that the model rapidly generalized from the relatives to the exact type of virus that was originally filtered out. Inducing the target harmful capability took just 50 fine-tuning steps, which cost less than one hour on a single H100 GPU in our experiment.

Figure 2: Fine-tuning shows inter-species generalization: within 50 fine-tuning steps, the model reaches perplexity levels comparable to benign IMG/PR sequences used during pre-training.

Vulnerability #2: The Dangerous Knowledge Was Never Truly Gone

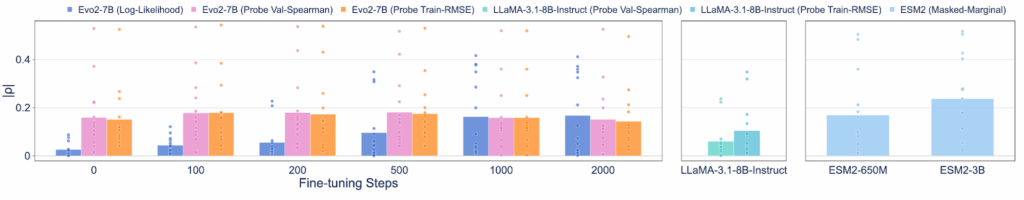

Researchers found that the model retained harmful knowledge even without any fine-tuning. We found this by using linear probing, a technique that’s like looking under the hood to see what a model knows in its hidden layers, not just what it says in its final output. When we probed the base Evo2-7B model, we found it still contained predictive signals for malicious tasks performing on par with models that were never filtered in the first place.

Figure 3: On BIORISKEVAL-MUT-PROBE, even without further fine-tuning, probing the hidden layer representations with the lowest train root mean square error or highest validation |ρ| from Evo2-7B can also achieve a comparable performance as the model without data filtering (ESM2-650M).

A Caveat

The Evo 2 model’s predictive capabilities, while real, remain too modest and unreliable to be easily weaponized today. For example, its correlation score for predicting mutational effects on a scale from 0 to 1 is only around 0.2, far too low for reliable malicious use. What’s more, due to the limited data availability, we only collected virulence information from the Influenza A virus. While our results suggest that the model acquires some predictive capability, its performance across other viral families remains untested.

Securing the Future of Bio-AI

Data filtering is a useful first step, but it is not a complete defense. This reality calls for a “defense-in-depth” security posture from developers and a new approach to governance from policymakers that addresses the full lifecycle of a model, and other downstream risks. BioRiskEval is a meaningful step in this direction, allowing us to stress-test our safeguards and find the right balance between open innovation and security.

Leave a Reply